The Gut Leads to Mental Health 2023

Psychiatry has changed significantly in the past century. We’ve moved from psychoanalytic conversation treatments to a neurobiological approach that combines psychotherapies with brain-targeting neurotransmitter medicines.

Psychotherapy and psychopharmacology surged quickly and damaged intellectual homeostasis.

I think another disturbance is underway.

As we reach the middle of the 2020s, new therapy methods are developing that use new insights into central nervous system (CNS)-body communication networks. As research has shown, these networks communicate extensively, showing that the brain’s immune system status is privileged but not inviolable.

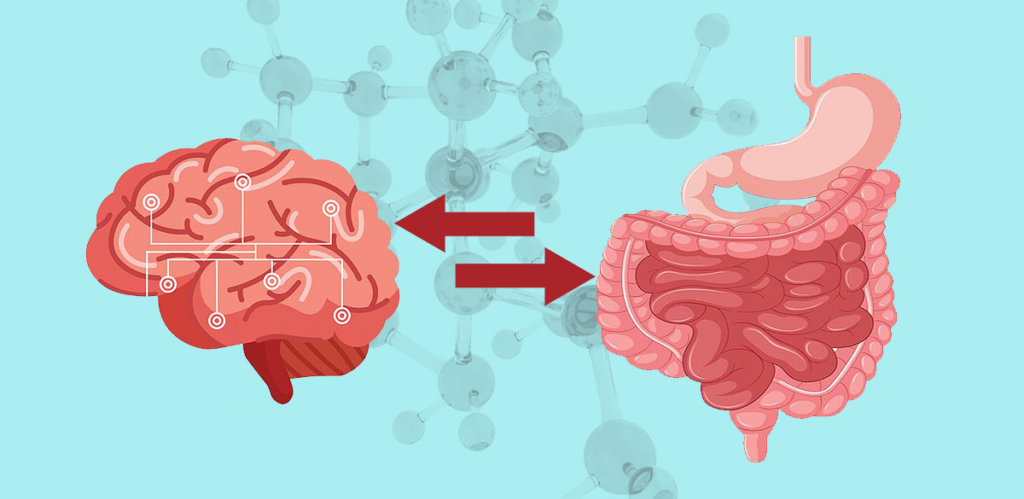

These findings also strongly imply that many mental diseases begin with gastrointestinal dysfunctions. Understanding these pathways helps psychiatrists treat patients.

Brain-Gut Microbiota

The GI tract has 100 million nerve cells from the esophagus to the anus. The GI tract contains at least 2,000 species of bacteria, archaea, fungus, protozoa, and viruses and 5 million genes and tens of trillions of organisms, mostly in the large intestine. Gut microbiome comprises these microbes.

More than 60% of a neonate’s microbiome originates from their mother. Genetics and environmental variables including nutrition, internal pH, and digestive enzyme concentration affect the gut microorganisms. One’s gut microbiome changes during life.

Despite this flux and change, the gut microbiota’s essential roles remain consistent. These include defending us from viruses, helping us absorb nutrients and minerals, and providing enzymes not included in the human genome that synthesize vitamins and metabolize polysaccharides and polyphenols. It synthesizes neurotransmitters, which go up the gut-brain axis to the CNS.

The stomach produces “runner’s high” dopamine, which the peripheral endocannabinoid system sends to the brain. In a 2022 Nature article, antibiotics interrupted this channel of communication, depriving mice of the dopamine surge and incentive to exercise.

This study partially explains why people have various exercise capacities, even if lab mice and humans have distinct motives. More significantly, it implies that substantial gut microbial alterations might impair gut-brain axis communication, altering behavior without our awareness.

Studies in rats that received feces from sad people showed signs of depression and anxiety and changes in tryptophan metabolism, suggesting that gastrointestinal changes might also affect mood.

Dysbiosis and Inflammation

Recent research suggests that the immune system mediates most of the CNS-gut crosstalk. Thus, gut issues may cause inflammatory GI illnesses including ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome and immunological dysregulation that leads to neurodevelopmental and behavioral disorders.

Unfortunately, there is no one microbial culprit causing all these disorders, thus no species can be targeted. Microbial profiles differ from gut to gut and are quite malleable, therefore there is no optimal profile.

Dysbiosis—unbalanced gut microbial populations—causes ailments, according to experts. A severe loss of microbial diversity, an overgrowth of troublesome bacteria, the removal of beneficial bacteria, or any combination of the three can produce this imbalance.

Dysbiosis can cause neuropsychiatric illnesses through vagal pathways, the endocannabinoid system, or the immunological system. Inflammation alters the blood-brain barrier, allowing inflammatory proteins to enter the CNS, disturb homeostasis, and cause neuroinflammation.

Neuroinflammation produces CNS structural damage and mental symptoms, including depression.

Thus, gastrointestinal issues might lead to mental health issues.

How Can We?

Over the past decade, researchers have traced these networks and steadily revealed the gut-immune-brain relationship.

They have frequently discovered that poor nutrition, sleep, and exercise cause dysbiosis, inflammation, metabolic problems, and neuropsychiatric diseases. Healthy eating, sleep, and exercise can avoid these diseases.

The concept of a “healthy diet” includes micronutrient-dense, high-fiber meals that foster a varied gut biome. Avoid simple sugars, refined flour, and saturated and trans-fat-laden processed meals.

Based on cutting-edge research, encouraging these dietary modifications can improve mental health in our patients.