Memories Aid Brains New Events Worth Remembering 2023

Memories are previous shadows and future brightness.

Recollections impact our worldview, attentiveness, and learning. Memories can change how we view future events and how much attention we pay to them. “We know that past experience changes stuff,” said UCSF neuroscientist Loren Frank. “It’s unclear how that happens.”

Science Advances has released part of the solution. Researchers studied snails’ ability to build new long-term memories of connected future occurrences. Their modest method altered a snail’s perspective of those occurrences.

David Glanzman, a cell biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles who was not involved in the work, said the researchers “down to a single cell” how previous learning affects future learning. “Using a simple organism to try to get understanding of behavioral phenomena that are fairly complex” was appealing to him.

Snails are basic, but the new discovery helps scientists comprehend the brain underpinnings of long-term memory in higher-order animals like humans.

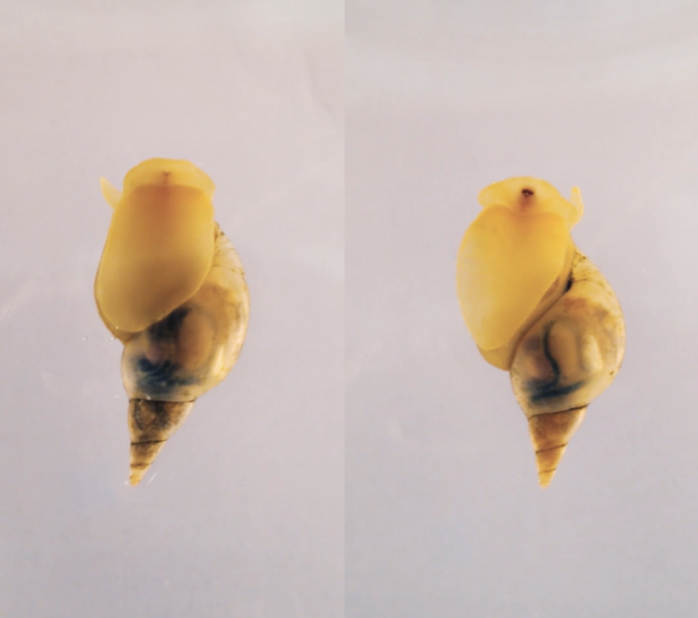

Crossley called the little foragers “remarkable learners” who can recall things after one encounter. In the current study, researchers examined snail brains to determine how they formed memories.

Conjuring Memories

Researchers trained snails with strong and weak training. They initially sprayed the snails with banana-flavored water, which they swallowed but spewed up after severe training. Snails devoured sugar afterward.

The snails learnt to identify the banana flavor with sugar from that one experience a day later. Snails swallowed water more readily after tasting it.

A poor training session in which a coconut-flavored wash was followed by a diluted sugar reward did not teach the snails this favorable link. Snails swallowed and spewed water.

The experiment was a snail version of Pavlov’s conditioning studies in which canines learnt to slobber when they heard a bell. Then the scientists examined what happened when they gave the snails a strong banana-flavored training followed by a weak coconut-flavored training hours later. Snails suddenly learnt from weak schooling.

The weak training failed again when done first. The snails remembered the intensive training, but it did not reinforce the preceding experience. Swapping strong and weak training tastes had no impact either.

The scientists found that vigorous training put the snails into a “learning-rich” period where the threshold for memory formation was lower, allowing them to remember things they otherwise would not have (such as the weak-training relationship between a flavor and dilute sugar).

This method might help the brain focus on learning at the right time. Food and danger may alert snails to surrounding food supplies and risks.Long-term memory development is “an incredibly energetic process,” said Michael Crossley, a senior research fellow at the University of Sussex and the study’s principal author. Brain cells require many molecules to form more enduring synaptic connections between neurons to form such memories.

Thus, to preserve resources, a brain must choose whether forming a memory is worthwhile. He stated it applies to human and snail brains.

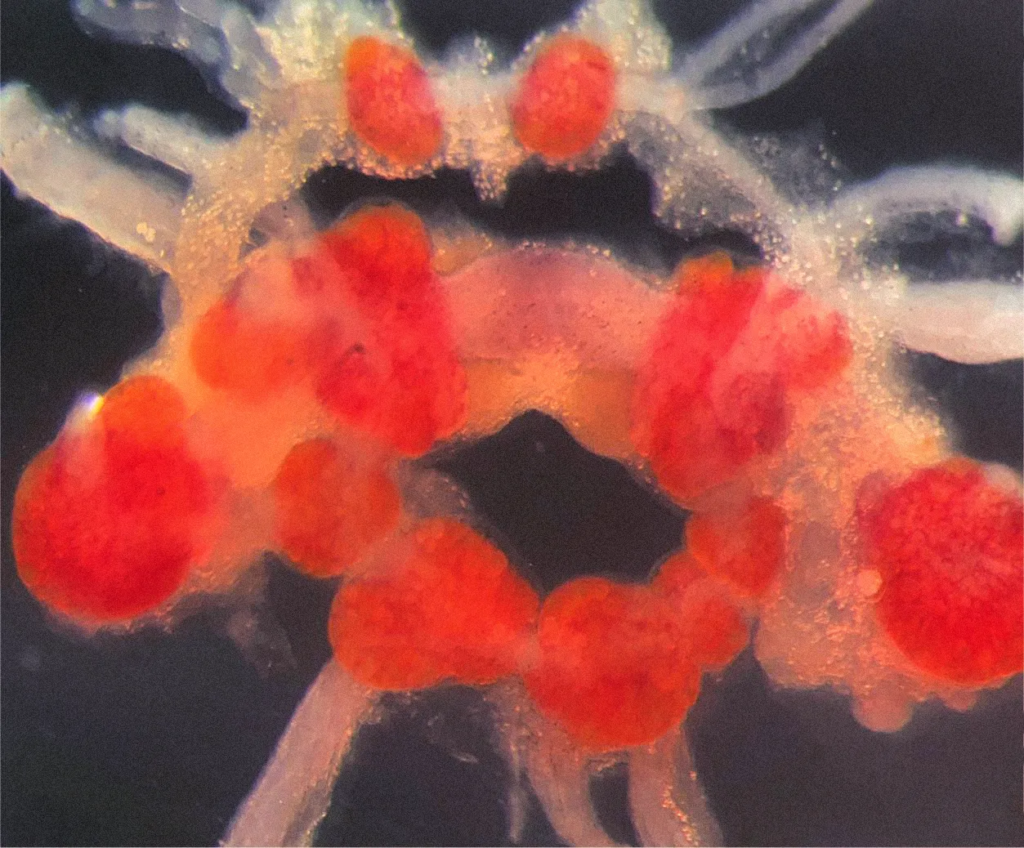

Crossley showed a thumb-sized Lymnaea snail with a “beautiful” brain on a video chat. The snail’s brain has 20,000 neurons, but each is 10 times bigger than ours and easier to analyze. Neurobiology researchers love snails for their large neurons and well-mapped brain circuits.

Crossley called the little foragers “remarkable learners” who can recall things after one encounter. In the current study, researchers examined snail brains to determine how they formed memories.

Conjuring Memories

Researchers trained snails with strong and weak training. They initially sprayed the snails with banana-flavored water, which they swallowed but spewed up after severe training. Snails devoured sugar afterward.

The snails learnt to identify the banana flavor with sugar from that one experience a day later. Snails swallowed water more readily after tasting it.

A poor training session in which a coconut-flavored wash was followed by a diluted sugar reward did not teach the snails this favorable link. Snails swallowed and spewed water.

The experiment was a snail version of Pavlov’s conditioning studies in which canines learnt to slobber when they heard a bell. Then the scientists examined what happened when they gave the snails a strong banana-flavored training followed by a weak coconut-flavored training hours later. Snails suddenly learnt from weak schooling.

The weak training failed again when done first. The snails remembered the intensive training, but it did not reinforce the preceding experience. Swapping strong and weak training tastes had no impact either.

The scientists found that vigorous training put the snails into a “learning-rich” period where the threshold for memory formation was lower, allowing them to remember things they otherwise would not have (such as the weak-training relationship between a flavor and dilute sugar).

This method might help the brain focus on learning at the right time. Food and danger may alert snails to surrounding food supplies and risks.

Frank isn’t convinced that the snails didn’t remember the inadequate training since they didn’t drink flavored water. He stated follow-up trials may be needed to distinguish between having a recollection and acting on it.

Glanzman noted mollusks and mammals like humans share learning and memory systems. Crossley said the authors had not seen this mechanism in people. “It may be broadly conserved and therefore deserves further attention,” he added.

Glanzman suggested studying how to permanently change perception. If snails are given an unpleasant stimuli, something that makes them ill instead of something they like, he thinks this may work.

Crossley and his team are interested in what occurs in snail brains when they do various activities, not simply opening and shutting their lips. Crossley called these animals intriguing. “These animals aren’t expected to do these kinds of complex processes.”